Okinawa is a peculiar place to be for an American, all the more so for an American who is not in the military. For World War II historians, 'Okinawa' evokes fierce and merciless battle between American and Japanese forces during the closing scenes of the Pacific Theatre; for American soldiers at the time, what is most likely remembered is the Japanese soldiers being ordered to commit suicide rather than surrender to the enemy; and to the Japanese of today, it evokes palm trees, pristine beaches and the continuing American presence in their country.

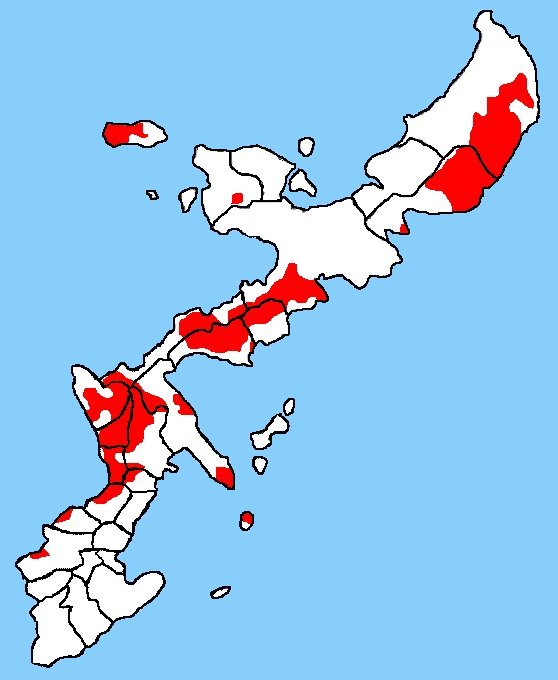

Okinawa was in fact an American possession until 1972, when it was given back to the Japanese. Despite this, nearly 20% of the main island of Okinawa-Honto is still occupied by American military bases, home to nearly 25,000 personnel.

This has not been an entirely happy residence. Numerous incidents, most recently just a few weeks ago, involving off-duty American soldiers committing crimes and accused rapes of Japanese girls have lead to serious protests to the American presence, though the pact that allows the Americans to stay was renewed a few years ago.

Even so, Okinawa remains an extremely popular tourist destination among Japanese (nearly 98% of tourists who come to Okinawa are Japanese, amounting to nearly 5.5 million people [!]), and with good reason: it is gorgeous.

Perhaps I should be more specific; Naha, the biggest city, capital, and transportation hub, is not gorgeous, particularly in the eyes of tourists who step off their flights ready for their tropical adventure. The main island is dominated by the American presence: used car lots advertising prices in both yen and dollars, numerous A&W franchises, and rumbling military caravans were common sights.

The unfortunate Japanese tendency to overdevelop hit southern Okinawa-honto hard. Blank-faced concrete buildings lined the coast, exhaust fumes from the broad highway that runs up the spine of the island filled the air, and the finest beach we could find within a 2-hour bike ride was a man-made one, somewhat mockingly named “Tropical Beach,” though despite the irony of hanging out on a South Pacific island on a man-made beach named Tropical Beach (why not re-name the island Tropical Island?), it felt pretty good to face the open ocean again.

Destined not to spend our “tropical” vacation in a clogged city (though to be fair it had it’s nice spots), Jerich, my travel partner, and I set off for nearby Zamami Island, a two-hour ferry to the west of the main island, with plans to camp on the beach.

Which we did, though we didn’t anticipate the nighttime temperature dropping to below 40 degrees. Even so, it’s hard to beat a campsite from which one can wake up and see this:

Or before going to sleep, see this:

Our second day there, we happened upon a very enthusiastic pair of girls on a graduation trip who invited us to where they were staying that night to hang out. This place, a minshuku, a traditional Japanese guesthouse, would be where we would end up staying the remainder of our trip. A communal experience, a few people would cook each night for all of the guests, who sat (on the ground) around a (low) table in the common room, talking into the wee hours. Given that we were foreigners, these late-night sessions included English lessons, covering a range of topics including proper usage of the phrase “god damn it,” and when it is appropriate to call someone an “asshole.”

The remainder of our time was spent meandering around Zamami and the other islands in the chain, biking, hiking, snorkeling, getting sunburned, and marveling at the fact that in getting away from “it all,” we might have accidentally discovered where “it all” was hiding in the first place.

These guard dogs, called Shisa, are ubiquitous in Okinawan houses, holdovers from the old Ryukyu kingdom. Normally found in pairs, one always has mouth closed, to hold the good spirits of the household inside, the other open, to allow the bad spirits to leave. This one was on top of the minshuku we stayed at.